Reflections from the Classroom: Students as Agents of Their Learning

by Rachel Goldner

December 9, 2025

The Forum is thrilled to feature the voices of educators who are seriously and passionately pursuing equity in mathematics learning for elementary students. In sharing their experiences in the classroom as well as their reflections, these guest bloggers offer readers a vision of what establishing and supporting an equitable math learning environment can look like in practice.

Rachel Goldner has 33 years of experience teaching across the elementary grades. She is currently a Math Specialist in the Lincoln Public Schools, supporting students in grades K-4. In this blog post she describes how she works to empower students to see themselves as agents of their own learning.

What I Notice about the Students I Teach

My kindergarten-fourth grade students have a range of skills; some they are proficient with and others they are still developing. When asked how they view themselves in math, most of my students say it’s difficult and that they’re not very good at it. Many rely on memorized steps and depend on others to help them choose strategies and evaluate their answers for reasonableness. This dependence is especially noticeable during classroom math time. During whole-class instruction, they rarely participate and often appear lost. When working independently, they frequently ask for help from adults.

My Goals for Students

I feel strongly about having my students take charge of their learning. I want to empower them as learners by focusing on what they already know and to develop strategies that make sense to them rather than rushing to find answers and moving ahead with what is next. I aim for students to look less often at me for assurance, correct answers and approaches and to instead look within themselves for how to solve problems.

My goal is for students to believe in themselves as problem solvers who can:

- dive into hard problems and say and believe, “I can do hard things!”

- consider revision of one’s thinking as something great mathematicians do

- devise a plan of action before solving a problem

- be reasoners who explain their thinking

I do not just consider myself a teacher of mathematics, but a teacher of effective learning habits that will carry over to learning and problem solving in all subject areas.

Working on My Goals

When students tell me they can’t do something because it is hard, I respond, “You can do hard things!” Last year, I was working with a first grader who was struggling with a number story involving the difference between two quantities. He turned red, tensed his body and scowled. He took me by surprise when he took a deep breath and announced, “I can do hard things Ms. Goldner!” and proceeded to move ahead and solve the problem. What a gratifying teaching moment!

Last year, I also took steps to build student confidence, agency, and self-advocacy by routinely helping students identify the many math skills they already had. I emphasized that each student has a bank of math knowledge and worked with them to pull out nuggets that connected with the problem at hand and build upon them. I worked with students to create several tools to support them in utilizing their math skills and knowledge to solve problems:

Use What You Know I posted a “Use What You Know” visual in my math office, which became a frequent mantra. Without speaking, I’d point to the visual, and students became skilled at responding with related math knowledge they possessed. I gave students small card copies to keep in class as reminders that they could solve many math problems independently.

Ask Yourself Questions When solving word problems, I use “Ask Yourself Questions” such as “What do we know?”, adapted from Grace Kelemanik and Amy Lucenta, to deepen thinking and reduce reliance on teachers for strategies and checking work.

“AYQs support productive struggle because they combat learned helplessness. When a teacher poses an AYQ, they provide students with a constructive thinking prompt, but more importantly, by not telling students what to do, they send the critical message that the student is capable of thinking and reasoning mathematically” (Kelemanik, G. & Lucenta, L. 2022).

Having AYQs posted, routinely asking them, and pointing to them has led students to internalize and ask them of themselves. This has led to students being more independent, intentional and empowered when solving problems.

Smart Mistakes In my sessions with students, I regularly use phrases like “smart mistakes” and “using tools is a sign of wisdom.” I praise students for identifying their errors and working to revise their thinking, reinforcing that strong mathematicians make mistakes and learning comes from revising. This has led to an increase in students feeling more comfortable acknowledging errors and a willingness to rethink their work.

Student-Specific Tools I learned that a key to students’ use of tools is involving students in creating them, revisiting them often, and reflecting on what was or wasn’t helpful. It’s powerful when students suggest revisions that improve the tool. It is important to introduce only one or two tools at a time.

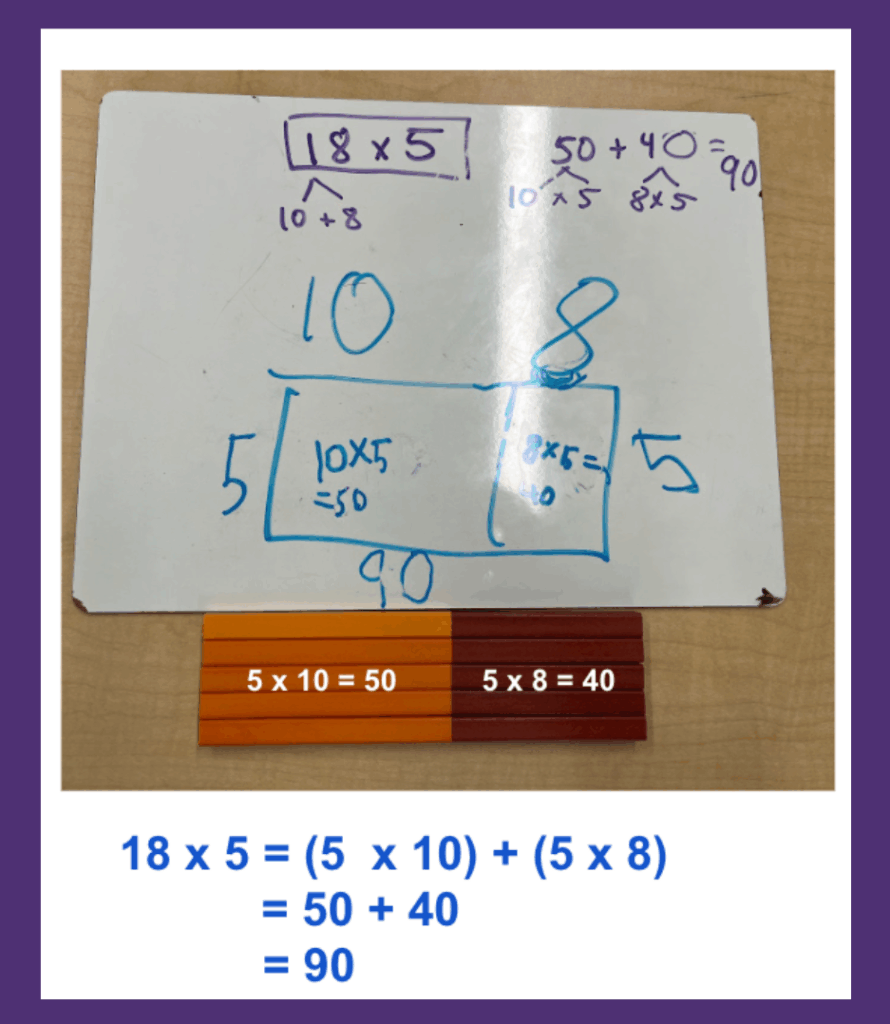

For example, I worked with a fourth grader who struggled to start math problems independently. Together, we created toolkits for multi-digit multiplication, division, and fraction concepts. The first tool we developed collaboratively was for partial products. During the initial sessions, after creating and adding to this tool, the student only used it with reminders and yet a couple of weeks later, the student was working on an end of unit assessment with his class and independently took out this multiplication tool. After that, I saw him share his partial quotient and fraction toolkits with peers.

Looking Ahead

This year, I plan to continue to empower my students to utilize what they already know to make sense of and solve problems as well as collaboratively create tools together for learning. A new goal is to increase student collaboration and engagement in more peer-to-peer discourse than teacher-to-student talk. My hope is for them to see themselves as valuable contributors to not only their own, but also others’ learning. I hope to see them eager to learn from peers, and to experience how cooperative work can increase both enjoyment and skill in math. I plan to explicitly let students know that each of their voices is of value and create an environment in which each student actively shares their thinking. We will also create a culture in which students respectfully respond to one another through agreement and disagreement. I am excited to see what transpires.

Stay tuned to hear more from Rachel about how her work continues to evolve this year.

Reference

Kelemanik, G. & Lucenta, L (2022). Teaching for Thinking: Fostering Mathematical Teaching Practices Through Reasoning Routines. Heinemann.